Patricia De Haven ’21

The Displacement of Nineteenth-Century Ideals of Womanhood as Seen by Portrayals of Young Women in Short Fiction Stories in Collier’s Magazine from 1902-1924

Patricia De Haven ’21

Major: History and Political Science

Minor: Asian Studies

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Darra Mulderry

My research centered on young women and their portrayals in Collier’s short fiction stories ranging from the early years of the twentieth century through the mid-1920s and how these depictions contrasted and compared to the values and expectations of the 19th century ideal of “true womanhood.”

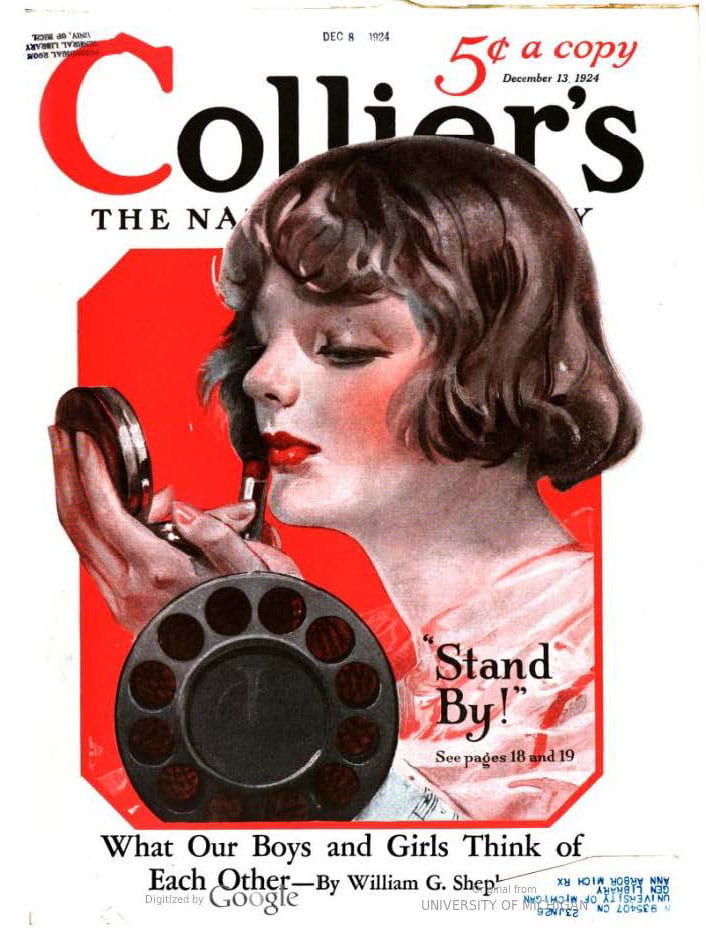

Research focused on editions of Collier’s from 1902-1903, 1912-1913, and 1924.

Evidence from the Collier’s magazine editions was compared and contrasted to Barbara Welter’s “Cult of True Womanhood” piece.

Using a collection of short fiction stories from Collier’s National Weekly magazine ranging from 1902-1924, the content centered on women evolves from a domestic narrative to a more public narrative, where women are professional, yet feminine, figures.

The attributes of True Womanhood consisted of: domesticity, piety, submissiveness, and purity. The woman, her husband, neighbors, and society judged her on how much she represented and practiced these values. A woman consisted of the roles of mother, daughter, sister, wife. Purity was one of the most identifying characteristics of a woman. Purity was the staple of femininity, without it women were unnatural and unfeminine. If a woman was unpious, she belonged to a lower order.

Domesticity was the most sanctified virtue a true woman could hold. From the home, women performed their highest duty of bringing men back to God. If a woman performed her duties satisfactorily, then her husband and sons would not need to indulge in immoral acts to compensate for something not received in the home.

World events and movements, such as war (as combat personnel), socialism, communism, and populist radicalism, were marked as inappropriate for women to enter and engage in. Those women who were involved disobeyed societal standards and expelled themselves from the pure sphere of true womanhood, The idea of shifting not only the gender hierarchy around, but also the economic, political, and social standing amongst men and women was offensive to nineteenth-century American gender ideals.

I found a short fiction story from 1902, written by female author Carolyn Wells, that follows a young, newly engaged young woman (Aurelia) who has experienced a recent shock to her wedding plans. The death of a family member also killed the financial source for the celebration. But, Aurelia’s dream is resuscitated by her Aunt Sarah. The gift from Aurelia’s aunt displays the power of a woman free of a man and his money.

In a Collier’s Illustrated Weekly fiction story in 1902, it is sensible to find a portrayal of a virtuous young woman because of its proximity to the nineteenth-century.

In the December 13, 1902 Collier’s Illustrated Weekly edition, the short fiction story “The Serio-Comic Governess” portrays a twist in one female character’s description. Author, I. Zangwill, provides background context for one of the protagonists, Eileen. Describing her mother, the audience is introduced to a woman that strays outside the bounds of piety, yet remains devout to her faith and her children.

While the mother teases around the idea of piety publicly, she is recognized for her faith by her children, who are unaware of their mother’s reputation. We can see how the ideals of nineteenth-century womanhood are reflected in this story. This woman’s place in society is lowered due to her lack of piety, but she is capable of salvation through her children.

In editions I analyzed in the next time period, 1912-1913, I uncovered a clear break from the content published ten years before. The October 26, 1912 edition includes a narrative that focuses on a local working girl, called “Playthings.” The protagonist, Maggie, and her story is revolutionary: the main character of the story is a young woman, employed, enjoying this sliver of activity in the public sphere, and usually without her father’s supervision. Maggie’s interests rebel against the attributes associated with the “Cult of True Womanhood,” most specifically Maggie’s zeal and dedication to her job. She is the public face of the shop, known by the neighborhood’s residents as a shopgirl. Instances of clashing behavioral expectations arise when Maggie’s father does not allow her to engage with some of his clients outside of the shop, restricted by her father’s rule, Maggie is not allowed to be photographed by any clients because it was too risque due to the notion he held that these artists engaged in scandalous activities and were inclined to fringe proclivities. Such taboo activities Maggie’s father disapproved of included smoking cigarettes and drinking wine. This attitude is indicative of a nineteenth-century mindset that did not allow women to perform “manly” activities, like smoking tobacco. While the photographers were appreciated clients, their environment was the antithesis of purity, and not appropriate for his quiet and virtuous daughter.

Participation in artistic endeavors would lead to Maggie’s loss of innocence and the ruination of her piety and other virtues. This dualism, the employed Maggie versus the innocent Maggie, is challenged and complicated as the story unfolds.

1912 editions of Collier’s were full of surprises and signs of transformation. The December 7, 1912 issue had a deafening symbol of Progressive-era imagery. An advertisement named “Please Do Your Christmas Shopping Early, Sincerely-The Girl Behind The Counter -A Suggestion” was published. This advertisement was the first instance I encountered where a young female was illustrated as a sale’s girl in a department store. This image conveyed what it was like to work in the public sphere, heightened by the difficulties associated with the holiday mass mobs. This depiction of a young female differentiated from previous advertisements featuring young women, (other such ads showed women cooking, for instance) and certainly offended the values emphasized by nineteenth-century society.

She was out in public, employed, and speaking to the masses. This image evoked a sense of empowerment because girls could imagine themselves as this shopgirl, stressed under the pressures of the holiday season, trying to appease the public on her own accord and hard work. It hinted at the future of commercialization, job practices, and equity, all supplemented by women.

A fiction story from August 30, 1924 presented the biggest opponent to the Cult of True Womanhood. This story, “Marriage in New York,” is quite shocking when placed alongside the expectations for female social behavior during the nineteenth-century. The story contradicts almost all of the advice collected by Welter in the “Cult of True Womanhood.” The story opens to the main characters, George Bingham, who is sitting in a cafe with his girlfriend, Madge Chickering. Madge and George work at the same advertising firm, in the same position, earning the same wages. This is a hugely significant shift in the portrayal of women in American society. Madge works alongside men in an office where she is respected enough to earn the same pay as her male colleagues. A story like this had never been printed in Collier’s before. It is a quintessential mark of an evolved life for a twentieth century woman. Madge is horrified by the thought of her grandmother’s life: restrained to her hometown, silenced, a prisoner to her home.

The author, Lucian Cary, outrightly points to the separate sphere and highlights the traditional notion that the home is a divinely created haven for women; not the office, which was created by corrupt, vile men. In this narrative, the separate sphere has been erased, the idea of being a wife and mother degraded, and nineteenth-century societal expectations are regarded as obsolete and offensive. Madge’s opinion on marriage is also distinctly different from traditional nineteenth-century perceptions. Instead of perceiving marriage as an institution that gives women a purpose, Madge views marriage as the cause for stagnation between couples.

If one looks at a nineteenth-century marriage, they will notice that it is a unification between an asexual female and an immoral man. As long as the wife satisfactorily completed her wifely and motherly duties, then her marriage and life were deemed fulfilling and all she needed. But such fulfillments were losing relevance and legitimacy.

Madge insists that the two will last longer as a couple if their personal freedoms are not infringed upon; the antithesis of nineteenth-century relationship patterns.

Industrialization reshaped the principles and expectations of the “separate sphere.” The turn of the century witnessed one in seven women as employed, mainly immigrant women.

Nineteenth century America was an era defined by repression, seclusion, dominance over the perceived weaker sex (women), and dependence on the stronger sex (men). Women were entities controlled by men. Marriage and motherhood lent a woman veiled purpose, significance, and legitimacy as a quasi-member of society. Women were not bred for individuality, personality, or strength. If these qualities arose, it was a consequence of the woman’s own development of character and actions. The radicalism that highlighted the turn of the century and into the 1920s shattered decades-old values, standards, and expectations for women. The turn towards liberation created a new kind of society. Women could have dreams, goals, and achieve unheard of possibilities, like earning the same pay as a man. Women did not need permission to enter into society, or need a man to chaperone their journey in the public sphere. Women earned the freedom to become functioning members of society.